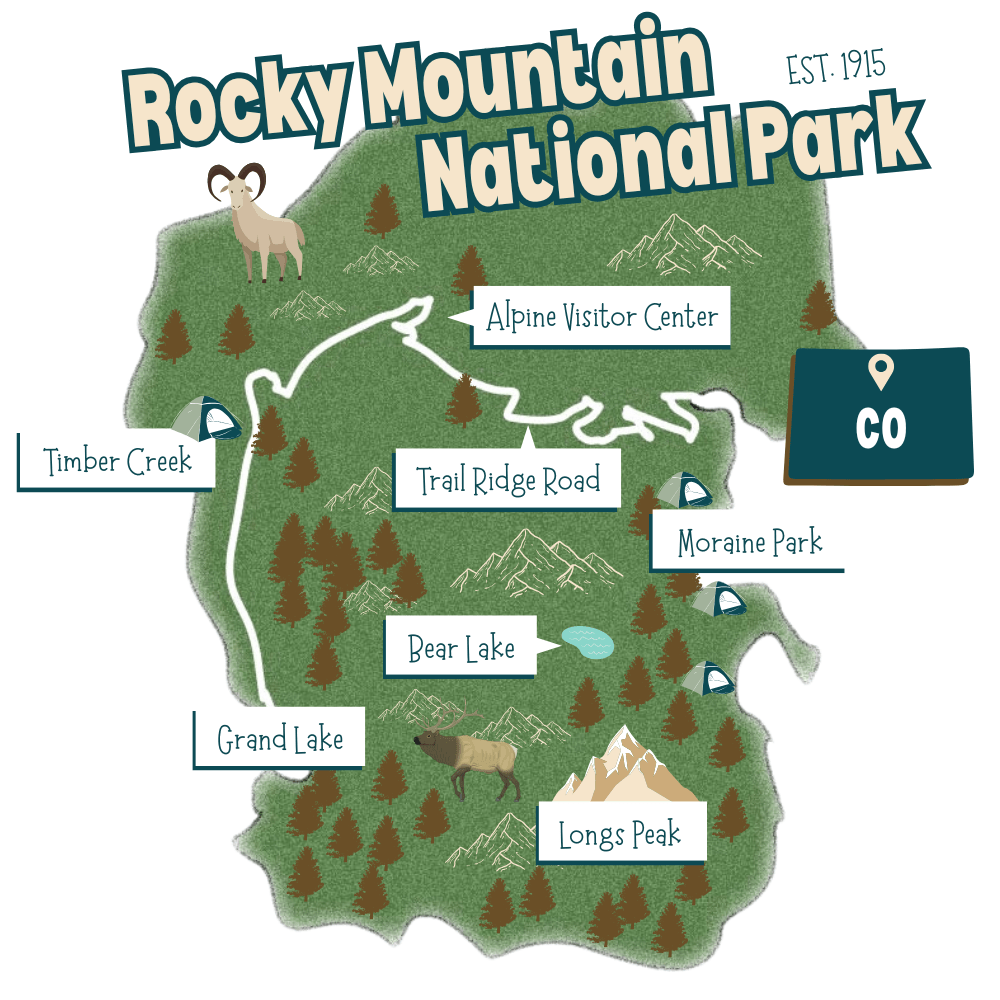

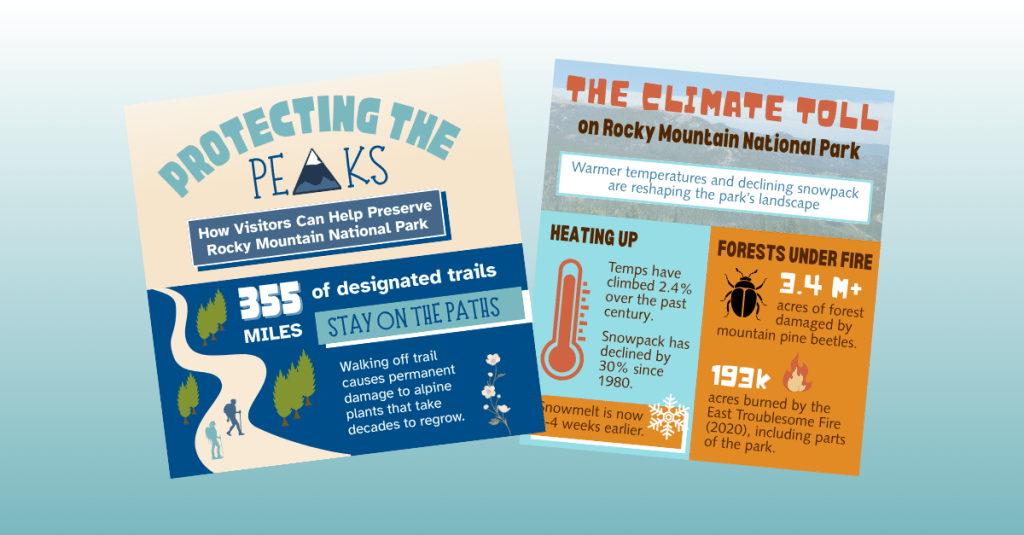

You’re deep into your passion project. The research is done, your ideas are flowing, and the deliverables are taking shape. For my project, Preserve the Peaks, a multimedia campaign about protecting Rocky Mountain National Park and encouraging responsible park visits, I’ve already created infographics, an interactive game, and a clickable poster in Genially.

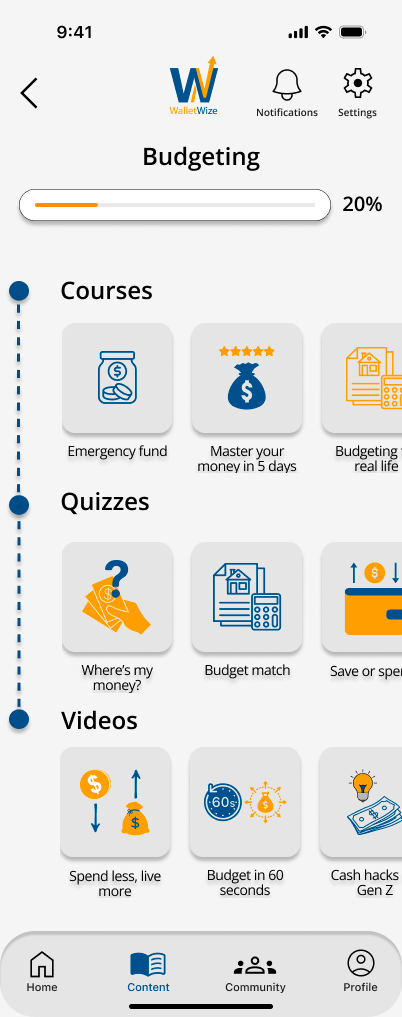

Now it’s time for my next challenge: building a digital PDF guide that’s both informative and fun to read. The goal? A go-to resource for anyone planning a trip to Rocky Mountain National Park, packed with relatable, easy-to-digest content that inspires visitors to both enjoy and preserve the park.

If you’re ready to create a digital guide that truly connects with its audience, let’s talk best practices.

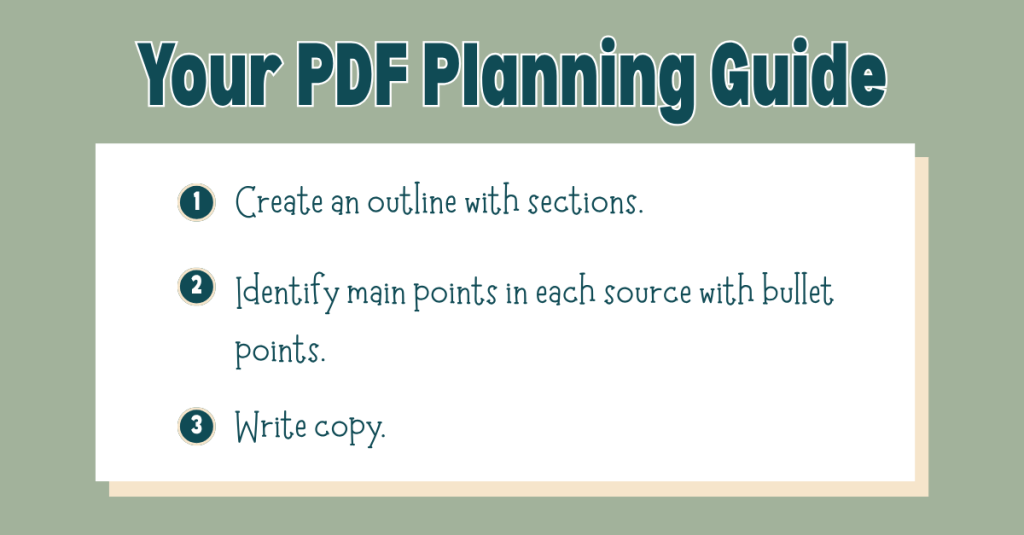

Start With Planning (and Then Plan Some More)

Here’s the first truth I learned: jumping straight into design without a plan is a one-way ticket to a messy, ineffective PDF.

Before I touched a single design element, I built a detailed outline of the sections I wanted to include. I based this outline on my research and my audience’s needs, and then I went through each source in my bibliography, pulling out 5–10 key facts, stats, or tips that could shape the guide’s copy.

This prep work meant that when it came time to write, I wasn’t staring at a blank page; I already had a roadmap.

My biggest takeaway: Give yourself more time for planning than you think you’ll need. That up-front investment will make the writing and design process smoother, faster, and far less stressful.

Want to see my own outline and research notes? Click here to view them.

Content First, Design Second

When you’re making something visually appealing, it’s tempting to start with design. But for a PDF guide to be effective, content is the foundation. The design should exist to enhance that content, not overshadow it.

In Best Practices for Accessible PDF Design, Albee highlights the importance of accessibility from the start. That means:

- Logical reading order

- Descriptive alt text for all images

- Strong color contrast

- Easy-to-read fonts

These features aren’t extras; they make sure your content can be enjoyed by everyone. If you wait until the end to think about accessibility, you’ll risk having to redo major portions of your guide.

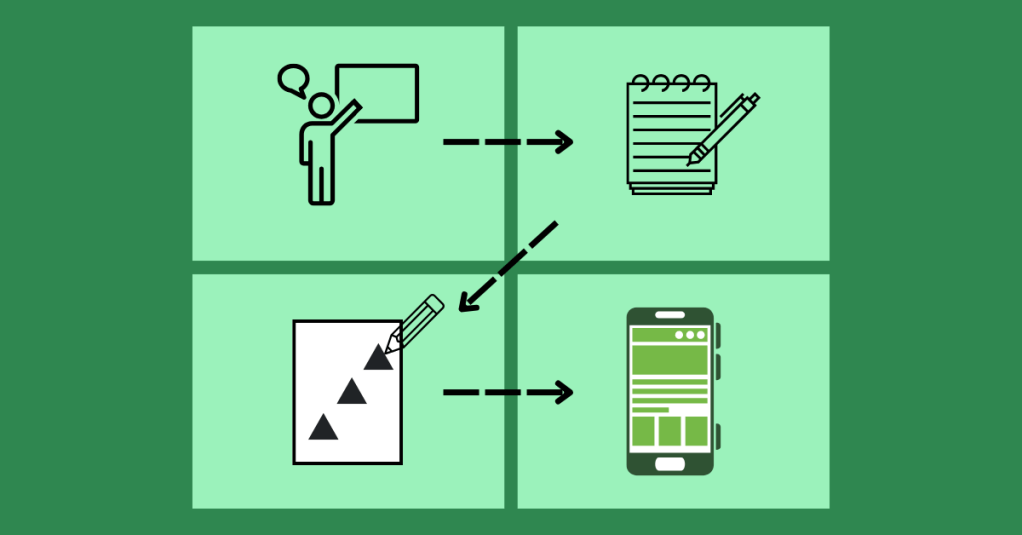

Make It Findable, Followable, and Scannable

In Findable, Followable, & Scannable: 3 Principles for Creating Clear Digital Guides, Jonathan DeVore breaks down how to create an effective PDF guide:

- Findable: Use search-friendly keywords, clear file names, and logical organization so your guide can be easily located online or on a device.

- Followable: Keep instructions clear and in the right order so your readers can easily follow along without getting lost.

- Scannable: Use headings, bullet points, and concise language so readers can quickly grasp the key points, even if they’re just skimming.

As I build my PDF guide, I will make sure each section is clearly labeled and packed with short paragraphs, bold subheadings, and sidebars for fun facts. That way, whether someone wants to read every word or just grab a quick tip, they’ll get value.

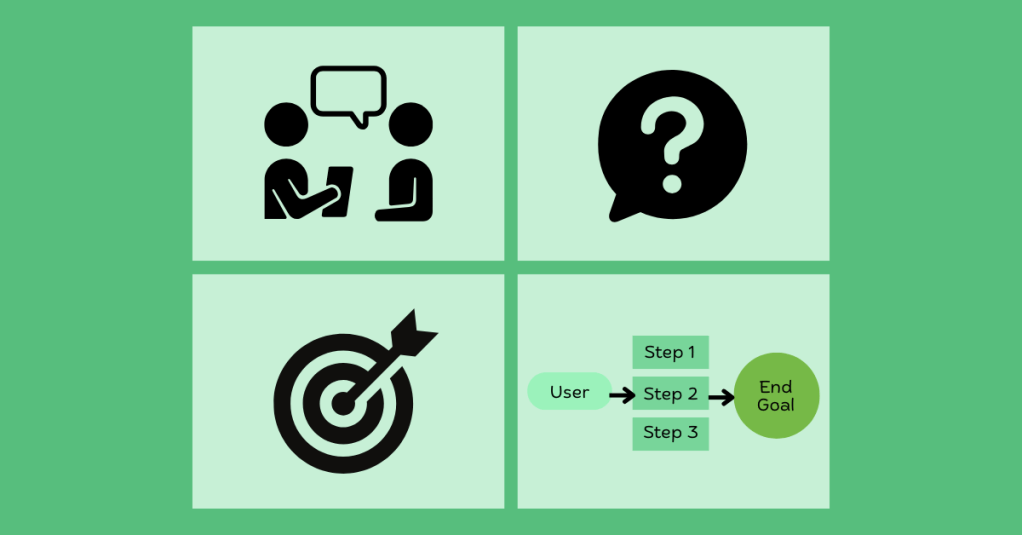

Always Keep Your Audience in Mind

This is the heartbeat of any good project: your audience is everything.

Ask yourself:

- What do they need to know?

- How do they prefer to read and absorb information?

- What tone will resonate with them?

For Preserve the Peaks, my audience is a mix of first-time visitors and returning nature lovers who care about the environment. That means keeping the tone conversational, using accessible language, and sprinkling in excitement about the park’s beauty with practical tips for responsible travel.

To view my progress on my digital PDF guide, click here.

Final Thoughts: Planning Wins Every Time

If you take away one thing from my experience, let it be this: plan first, design second.

A well-planned guide flows naturally, communicates clearly, and invites readers to explore every section. Combine that planning with thoughtful accessibility and design choices, and you’ll have a PDF that’s not only visually appealing but also memorable and easy to use.

Whether your goal is to inspire travel, teach a skill, or share important information, your guide has the power to connect deeply with your audience.

So grab your notes, outline your ideas, and build something worth reading. Your audience is waiting.

Happy creating!