Low- and high-fidelity prototyping from The Product Manager.

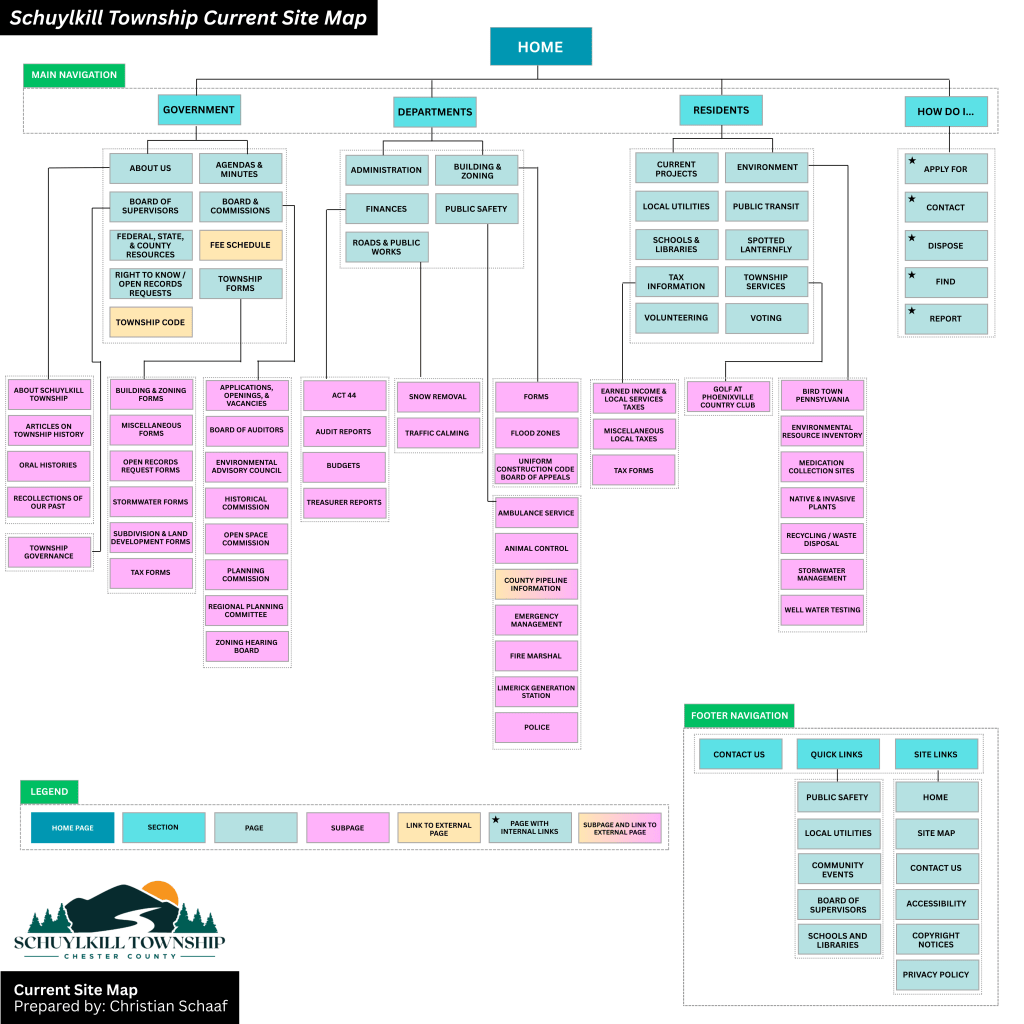

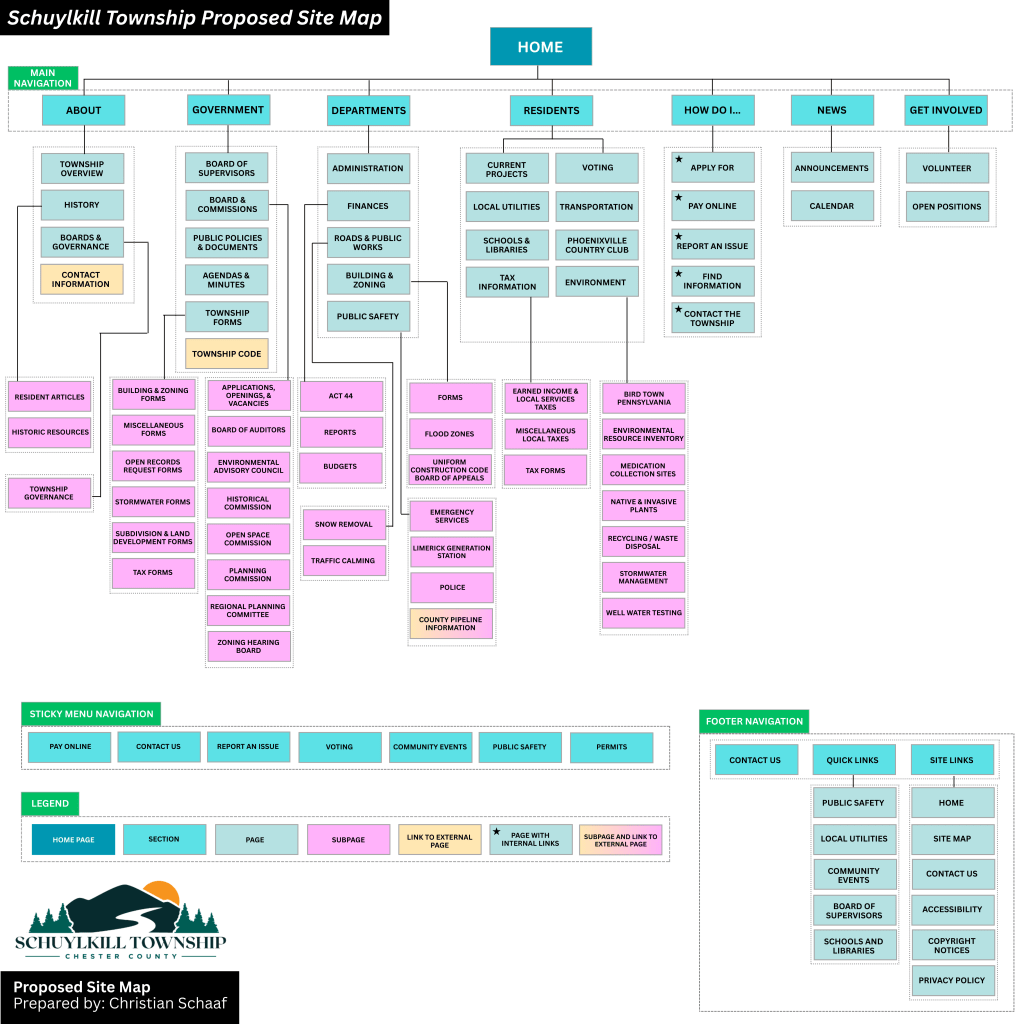

Have you ever looked at a mobile app and thought, “How did someone design this?” Behind every polished interface is a long journey of research, ideation, testing, and lots of prototyping. During my recent experience designing a companion app for Schuylkill Township’s website, I discovered how high-fidelity prototyping transforms concepts into tangible, testable designs. Let’s walk through what I learned and why fidelity in prototyping matters more than you might think.

Understanding Prototype Fidelity: Low vs. High

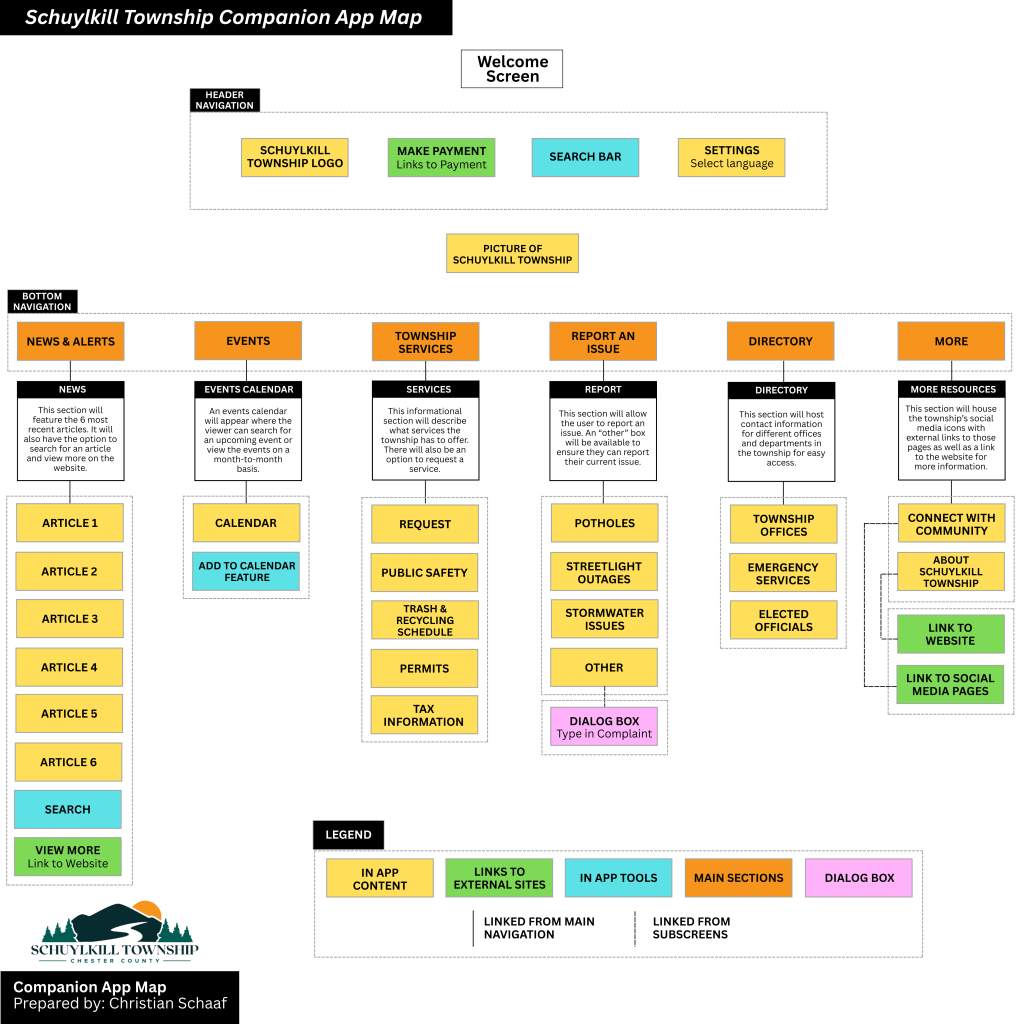

Not all prototypes serve the same purpose. When I first started this project, I didn’t realize that “prototyping” could look so different depending on the stage of design. In her article Low-Fidelity vs. High-Fidelity Prototyping: Key Differences Explained, Iulia Sorodoc describes that fidelity in prototyping is measured across three levels: low, medium, and high.

Low-Fidelity Prototypes

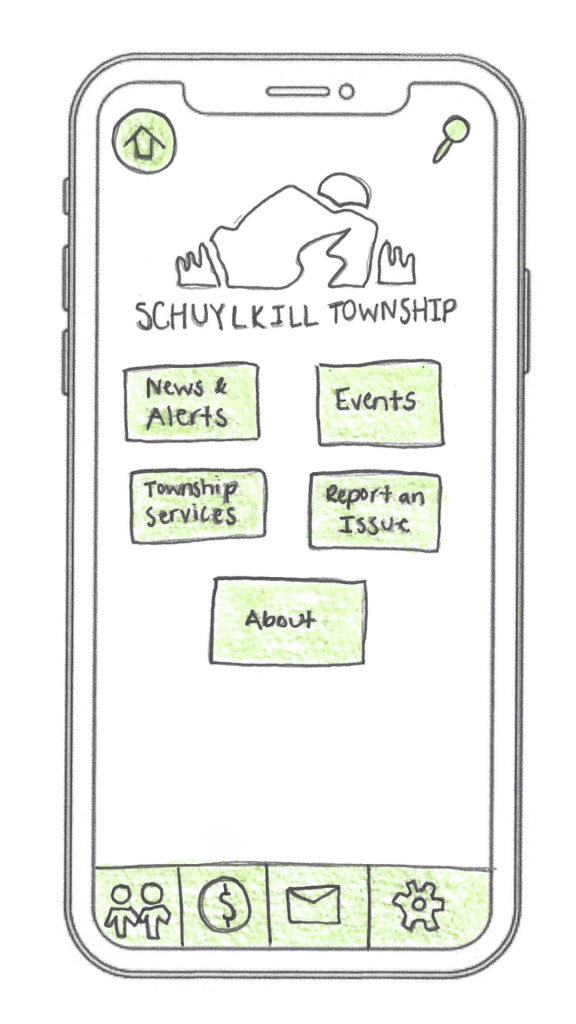

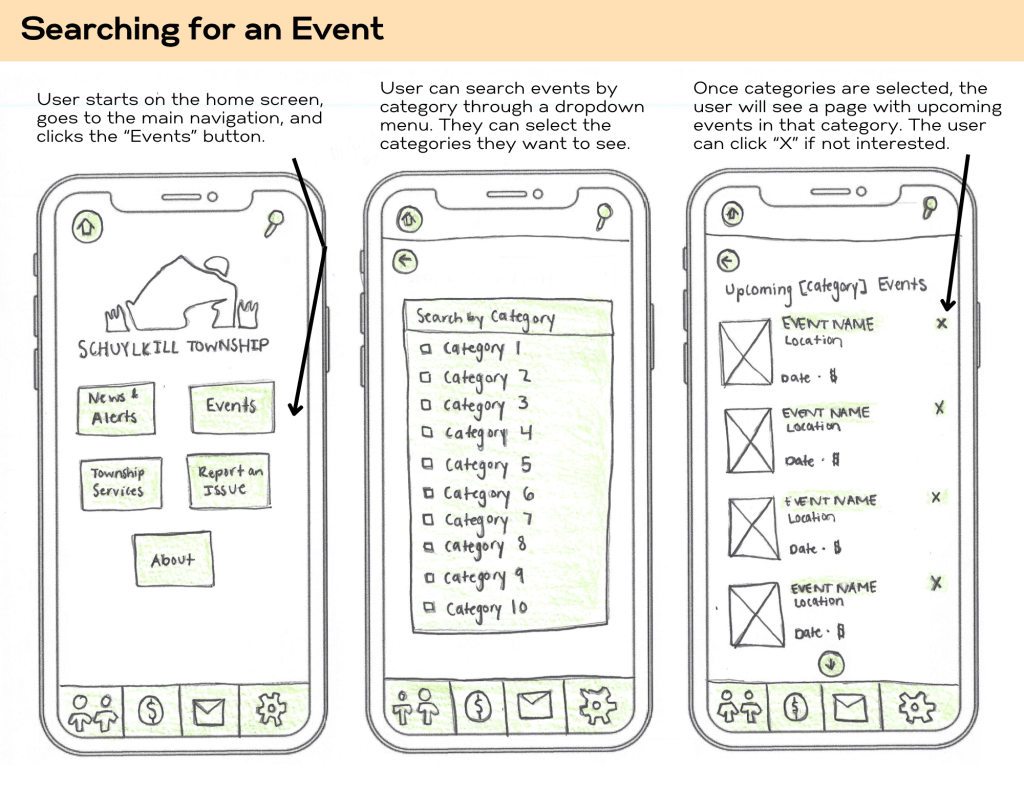

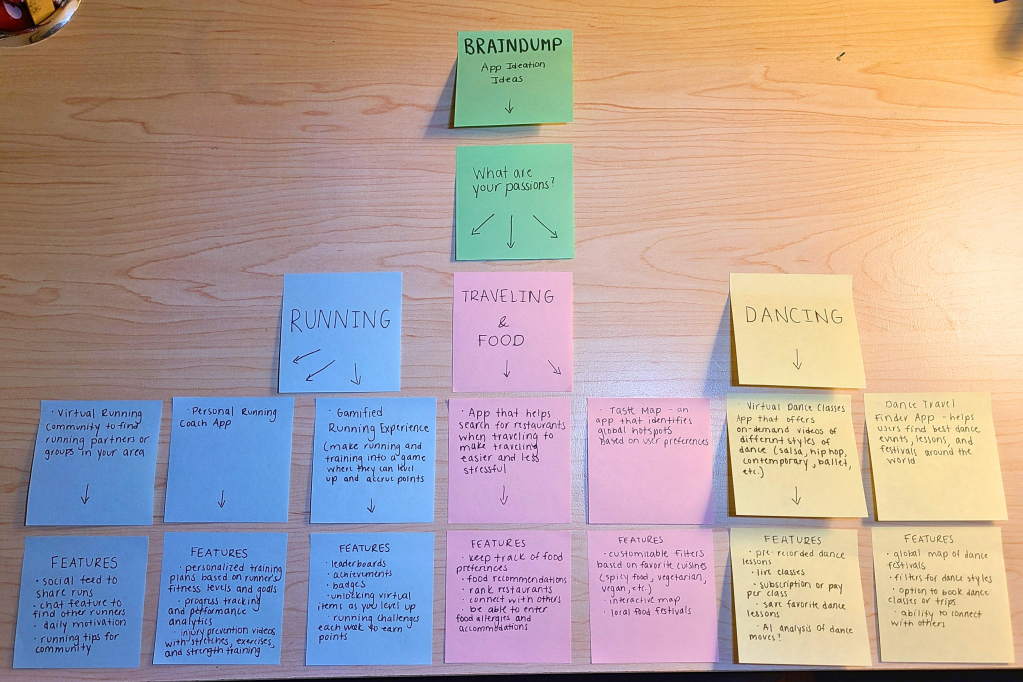

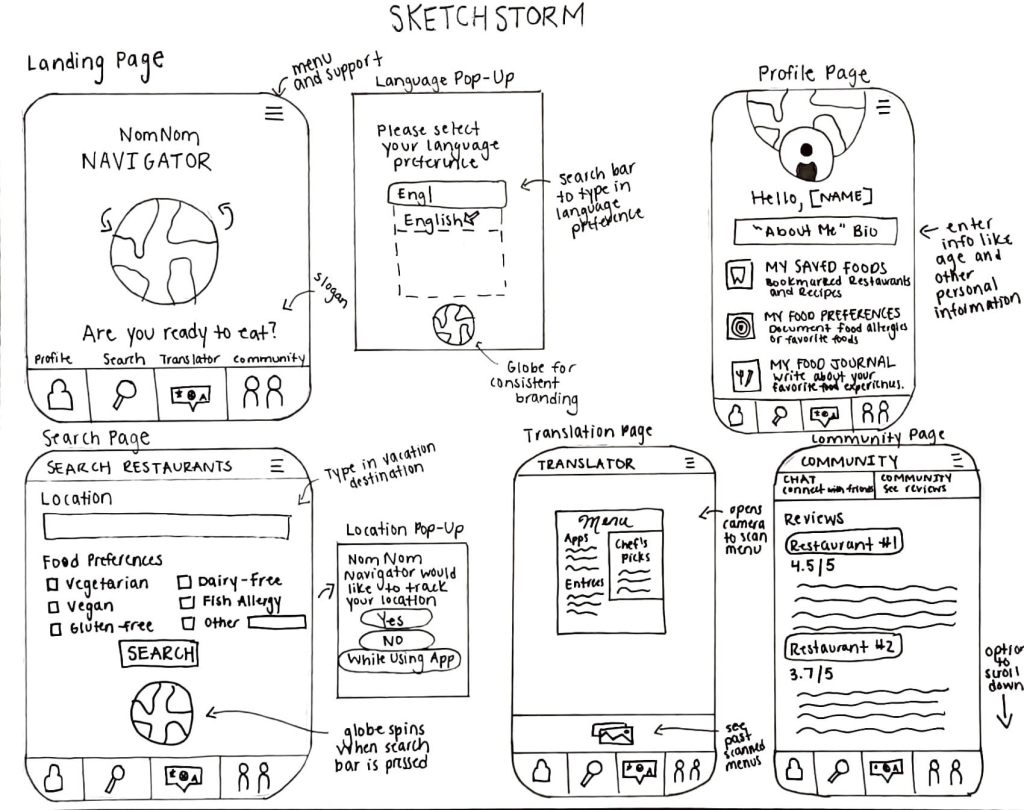

Low-fidelity prototypes are simple, often hand-drawn sketches. They focus on layout and flow rather than visuals or interactivity, making them perfect for early-stage brainstorming. Low-fidelity prototypes are quick and inexpensive to produce, making them ideal for early-stage design. However, they have some drawbacks: they offer limited interactivity, don’t closely resemble the final product, and can make it harder to gather meaningful user feedback.

An example of low-fidelity prototyping from my project.

Medium-Fidelity Prototypes

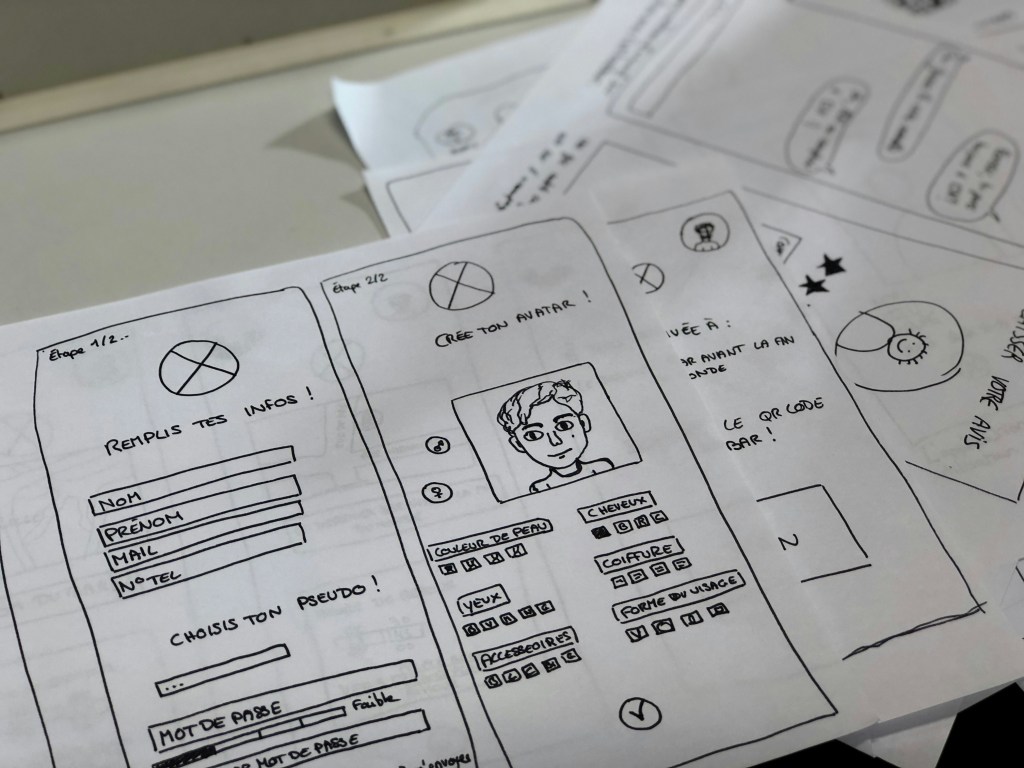

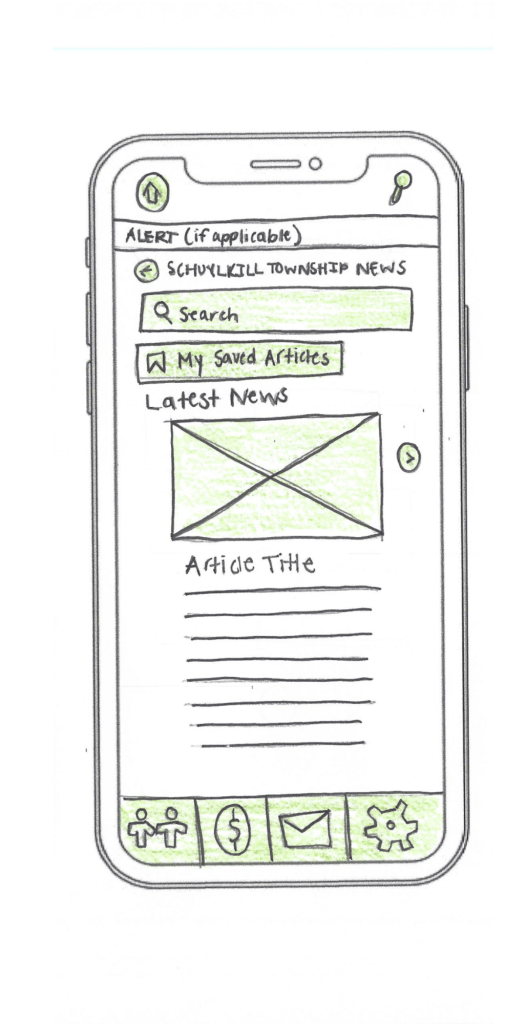

Medium-fidelity prototypes offer more accurate layouts, include some user interface (UI) elements, and may have basic interactive components. They strike a balance between realism and flexibility.

An example of medium-fidelity prototyping from mentormate.

High-Fidelity Prototypes

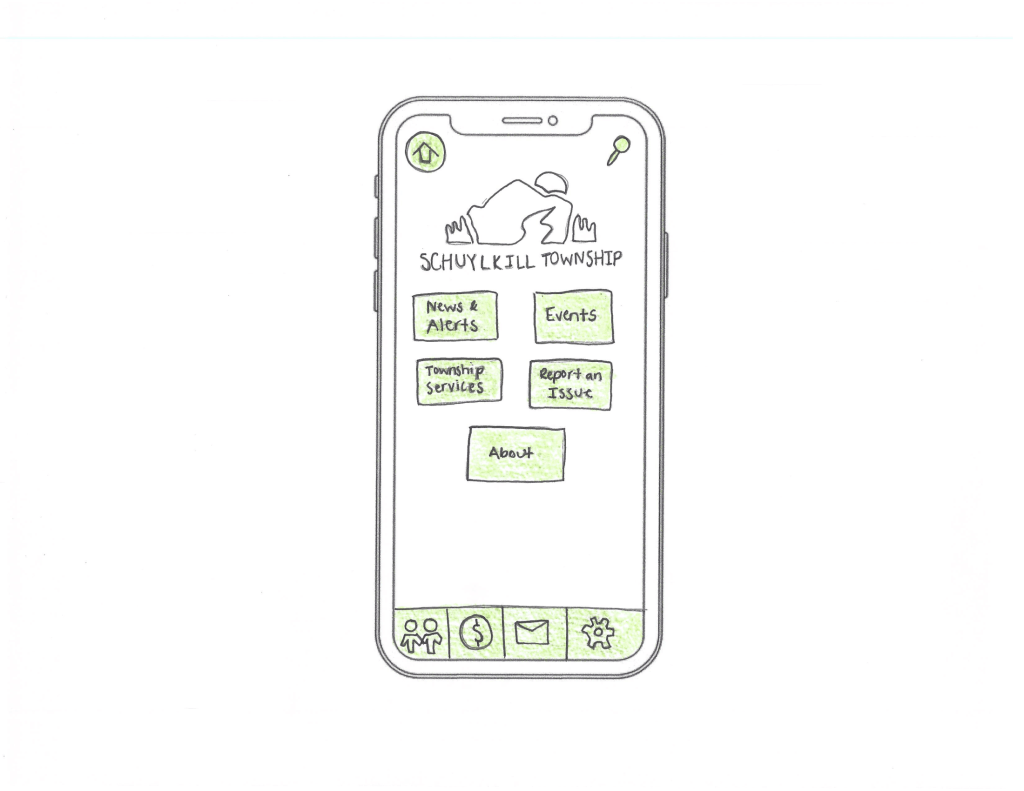

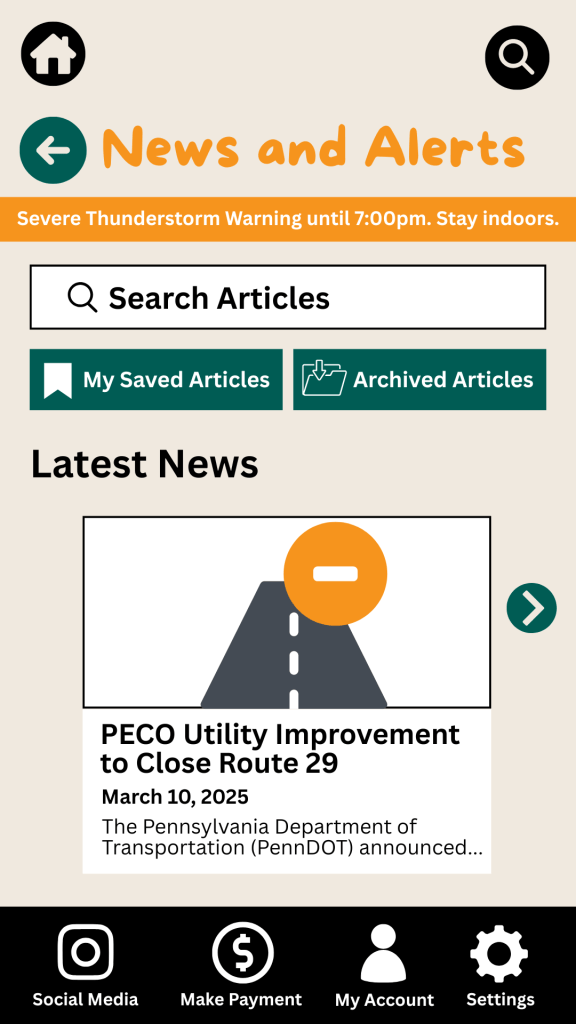

High-fidelity prototypes, on the other hand, are polished and realistic. They replicate the final product as closely as possible with detailed visuals, real content, and full interactivity. They take longer to build, but the payoff is in their ability to simulate the real user experience.

An example of a high-fidelity prototype from my project.

The level of fidelity you choose depends on where you are in the process and what kind of feedback you’re looking for. In the early stages, rough sketches suffice. But as you move closer to development, a more refined prototype is key to gathering accurate user feedback.

Prototyping Tools for UX Designers

When it comes to choosing the right prototyping tool, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. As Fahim Bin Omar outlines in his article Best Prototyping Tools for UI/UX Designers – How to Choose The Right One?, your ideal tool depends on a few important factors, including your design goals, the complexity of the project, the level of fidelity you need, how well the tool supports collaboration and feedback, its compatibility with other software you use, and device support and accessibility.

Popular Prototyping Tools to Consider

There are many programs that UX/UI designers use to create interactive prototypes. Some of the best include:

- Figma: A cloud-based favorite among teams for its real-time collaboration features and comprehensive prototyping tools.

- Marvel App: Known for its user-friendly interface and ease of turning static designs into interactive prototypes.

- Adobe XD: Great for those already in the Adobe ecosystem, offering seamless integration with other Creative Cloud tools.

- Sketch: A powerful Mac-based design tool with an intuitive interface and a wide range of plugins.

- Proto.io: Lets you create realistic, code-free prototypes right in your browser with a simple drag-and-drop interface.

- Webflow: A unique option for those who want to build responsive web prototypes with real HTML, CSS, and JavaScript output.

Whatever you choose, make sure it aligns with your needs. Remember: The user always comes first. The right tool should help you design for clarity, accessibility, and ease of use.

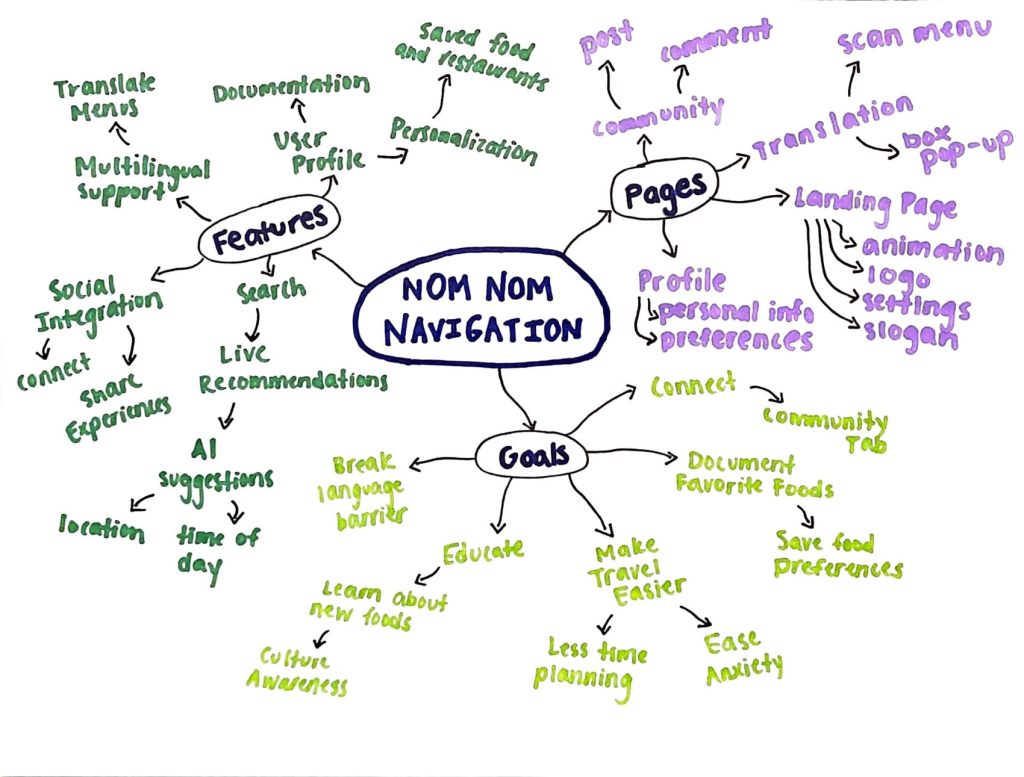

My High-Fidelity Prototypes

For this project, I used Adobe Creative Suite to design the visual elements of my prototype and then brought it to life interactively using the Marvel App. Since I already had a subscription to Adobe and was familiar with both tools, I was able to focus more on creating a seamless and user-centered experience.

While I explored several platforms, Adobe and Marvel gave me the flexibility and control I needed to produce a highly usable and visually engaging prototype. View the video below as I walk through each prototype I created for the Schuylkill Hub app.

Changes from Low- to High-Fidelity Prototypes

Once I began user testing last week, it became clear that a few areas of my prototypes needed improvement. One of the most notable pieces of feedback was confusion between the “Contact” and “Township Services” sections. Users weren’t sure where to go for help.

To fix this, I combined both into a single, clearly labeled section: Contact Township. This new layout provides an easy-to-navigate overview of township services along with direct contact options for each department, improving both clarity and accessibility.

I also made several updates to the footer navigation based on additional user feedback:

- Added “My Account” and “Settings” so users could access personal information and preferences quickly.

- Included labels beneath icons to make navigation more intuitive.

In the News & Alerts section, I implemented several new features:

- A top bar for urgent alerts.

- A personalized “Suggested for You” section.

- An “Archived Articles” button for past content.

To make the prototype feel authentic to the township, I included local events and headlines, and built out supporting features such as a search bar, an ‘About’ section, and a ‘My Account’ page.

Click here to view each step of the process of creating the Schuylkill Hub app.

Reflection

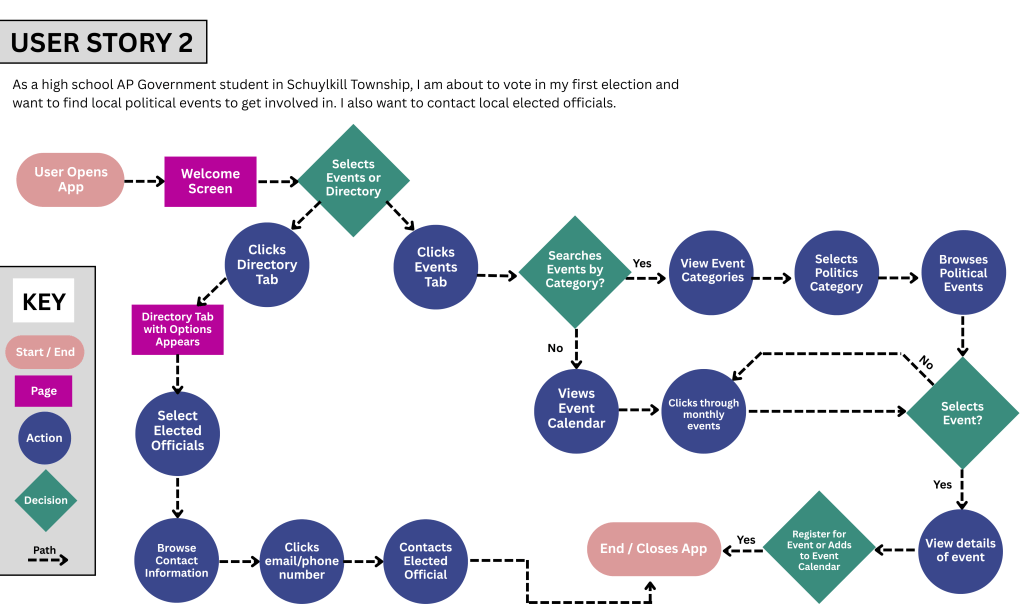

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from this project, it’s that prototyping is where ideas truly start to take shape. From low-fidelity sketches to interactive high-fidelity designs, each version helped me refine my app’s user experience through iteration and feedback.

In the early stages, my low-fidelity prototypes were just simple outlines that mapped out the app’s basic structure and flow. These were invaluable for quick brainstorming and helped me think through how users would navigate the app. Because they were easy to change, I could revise layouts based on feedback without feeling too attached to one idea.

As I moved into medium- and high-fidelity prototypes, the process became more detailed and intentional. Visual hierarchy, color palette, typography, and real content began to shape a more complete picture of the app.

Looking back, I now see prototyping as a form of communication — a way to translate abstract ideas into something tangible, testable, and ultimately user-centered. It’s not just about making things look good; it’s about making things work well for the people who use them.

I’m walking away from this project with a much deeper appreciation for prototyping as an essential part of the UX design process. The experience has taught me to approach every project with curiosity, openness to feedback, and a commitment to designing with the user in mind.