Have you ever worked on a task, however miniscule or large it may be, and felt overwhelmed because the solution wasn’t clear? If you answered yes, you’re not alone. I’ve been there too. The old me would hyperfocus on finding a solution immediately, growing frustrated when it wasn’t within reach. Now, even though I sometimes succumb to this irritation, I try to approach it differently.

In Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again, Johann Hari introduces the concept of mind-wandering, a practice modern society often dismisses as ineffective. We’re constantly told to be productive, so why would we “waste” time letting our minds drift? With the internet at our fingertips constantly bombarding us with information, the idea of slowing down feels counterproductive. But maybe, there’s a hidden benefit to mind wandering.

Professors Nathan Spreng and Jonathan Smallwood, along with Samuel Murray, Nathan Liang, Nicholaus Brosowky, and Paul Seli in What Are The Benefits of Mind Wandering to Creativity?, have all explored the potential advantages of mind-wandering. Their studies suggest that allowing your mind to wander can help you organize personal goals, tap into creativity, and make better long-term decisions. They also highlight how the environment affects the quality of mind-wandering—while a stressful setting may lead to negative results, a calm, peaceful space can lead to breakthroughs in inspiration and solution.

I was surprised when I first encountered this idea. Society often teaches us that being productive means staying laser focused, digesting endless streams of information, and avoiding distraction. I had always viewed mind-wandering as an unproductive, off-task mental process. But then I asked myself, have I ever experienced this kind of wandering before?

The answer is yes. When I was younger, after spending hours on schoolwork and growing frustrated, my parents would say, “Christian, take a break. Go outside and clear your mind.” I didn’t realize it then, but that simple advice helped me unlock the mental clarity I needed.

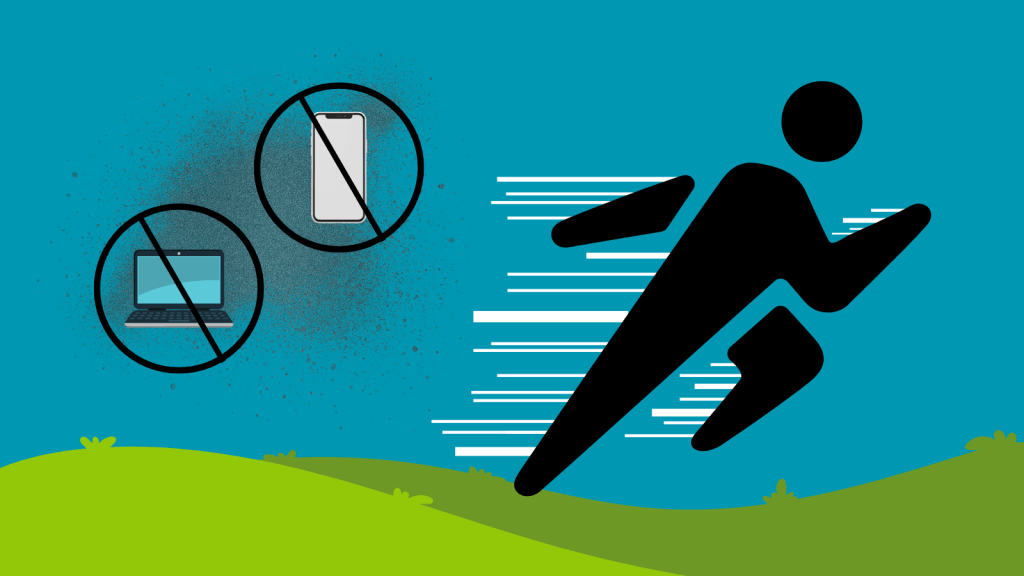

As an adult, the one activity that consistently allows me to experience mind-wandering is running. When I run, I enter what Hari calls a “flow state.” I feel alive, present, and free. The world slows down. I hear the birds’ songs, admire the flora and fauna I run past, feel the rhythm of my feet hitting the pavement, and appreciate the everchanging architecture around me. My mind drifts—freely, effortlessly—and in these moments, solutions to life’s problems often appear.

It’s in this tranquil setting that my mind can wander without pressure, and as the research suggests, the benefits are profound. Like Hari’s mind-opening experience in Provincetown, my thoughts become clearer, my creativity heightens, and I find peace.

So maybe Hari and the experts are right—slowing down and allowing our minds to wander isn’t unproductive. In fact, it may be the key to solving the complex problems we face in life.

Leave a comment